I have always been fascinated by maps. As a child, I had maps pinned all over my bedroom walls. Maps of country towns, road maps, a map of the world with the Empire and Commonwealth still marked in red as it was on the little globe of the world. Then there were the many atlases around the house of varying ages, some dating back to my parents’ childhood with their political boundaries of now van ished countries.

ished countries.

On wet Saturday afternoons, Brother David and I would sort our stamps, counting them, putting them in order. Here we used the Stanley & Gibbons catalogue as a basic resource, Again, it was a geography and history lesson. This is the first Confederate postage stamp showing Jefferson Davis and placed in circulation in October 1861, five months after postal service between the North and South had ended.

This love of maps carried through into an interest in geography despite the sometimes boredom at primary school of having to draw maps of Australia or NSW with the rivers and boundaries carefully marked. Indeed, at one point that interest was so great that I expected to major in geography at university.

That was not to be. I was more interested in human rather than physical geography, The broad introductory nature of that first year course simply didn’t grab. In fact, I found it quite boring. I therefore put geography aside for history and economics, although my general interest in the subject continued.

Despite my interest in maps and in geography, my sense of spatial awareness was not well developed. By spatial awareness, I simply mean the geography of a place or area; size, distances, rivers, plains and mountains; I understood in a general abstract sense, but I didn’t feel it. This was a bigger weakness than I realised at time.

I am not a geographical determinist, but life is shaped by geography.  I was researching and writing on the history of places and periods when I didn’t actually properly understand the geography. These are the ruins of Ancient Thera on the Greek island of Santorini. It took a visit to the Greek Islands in 2010 for me to begin to properly understand the geography involved, including the importance of water; water to sail on, water to drink.

I was researching and writing on the history of places and periods when I didn’t actually properly understand the geography. These are the ruins of Ancient Thera on the Greek island of Santorini. It took a visit to the Greek Islands in 2010 for me to begin to properly understand the geography involved, including the importance of water; water to sail on, water to drink.

Just as I didn’t properly recognise my limited spatial awareness, I didn’t recognise the way that those maps I loved were affecting my sense of geography, creating hard lines in my mind based on boundaries and human constructions such as railway lines. Those lines helped determine what I looked at, how I interpreted things. Actually, the world wasn’t like that at all. Our obsession with hard lines, with order, actually distorts the way we see the past.

Today, we have a further very particular problem. Modern communications and transport patterns are actually destroying our sense of spatial awareness. The loss of MH70 is a case in point. There was genuine surprise at our inability to find the plane. People had simply forgotten how big the Southern Indian Ocean is.

Our diminishing sense of spatial awareness combines with our interest in lines and maps to change the mental mudmaps we use to interpret the world. We see the world in terms of a series of dots linked by lines along which we travel. While the length of those lines is determined by travel times, instant communications effectively compresses the dots. The world outside those dots and lines progressively vanishes from our consciousness.

If you look, you can see this effect in operation in your own world.

Do you use Google maps? Ten years ago, you would have got a road map or street directory to plan your trip. You would have had to check the route in some detail, work out where to turn etc. Now many people rely on the GPS system and just do as they are told. It’s convenient, but it means that at the end of your trip your knowledge of the route is far less than it once would have been.

As an alternative, consider the expressway. Even twenty year ago, you would have wound through towns and villages, stopping as required. Today, the modern expressway bypasses all those places, with people stopping at the now ubiquitous service centres. The towns and villages that you once knew are progressively being expunged from memory unless, of course, you have a particular personal or business reason to go to them.

These issues are on my mind at present for a number of reasons, partly professional, partly personal.

These issues are on my mind at present for a number of reasons, partly professional, partly personal.

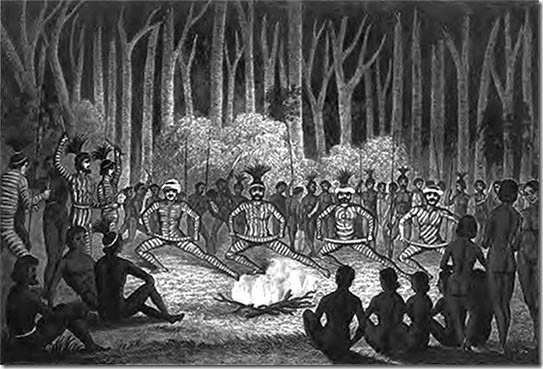

The recreation of the Aboriginal history of what is now Northern NSW before 1788 is like putting together a jigsaw made up of many fragments. It is not possible to be definitive, merely plausible. So long as you provide your evidence, your story can then be challenged by others.

I am often asked how do I know, how can I know, what is my evidence? Part of the answer lies in the archaeological record, the material that survives from various periods of the long Aboriginal occupation of this continent. Part comes from early settler records or ethnographic studies. This material dates from the time of disruption and poses many problems, not least of which is our inability to draw any certain connections between the the position at the time of European intrusion and that holding in past aeons. This problem become progressively more intense the further back into the past we go.

A further complication lies in the way in that Aboriginal history, our views of the Aboriginal past, have acquired accretions, barnacles if you like, from evolving perceptions of that past within the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities alike. People always re-interpret history to suit current needs. It can be extremely uncomfortable for both historian and reader where the evidence fails to support or even conflict with current beliefs.

Geography is central to any navigation of this mine field. In his 1832 book, the writer William Breton refers to Corborn Comleroy as the name given to the large area occupied by what we would now call, among other things, the Kamilaroi. He notes that the Corborn Comleroy travelled to Port Macquarie for ceremonies. So far so good, but where did they come from, how did they get to Port Macquarie, what does it tell us about links?

The Kamilaroi language group occupied a large swath of inland NSW from the Upper Hunter probably into what is now Queensland. Michael O’Rourke considers that those attending the Port Macquarie ceremonies would have travelled from the Mooki or Peel Rivers up onto the southern tip of the New England Tablelands through the Nowendoc district, across the tributaries of the Manning River to the Ellenborough River and then down to the Hastings. This makes sense, but only if you know the complex geography of the area.

It is, by the way, remarkably difficult to avoid errors in all this. The Wikipedia entry on the Manning River given above suggest that the traditional custodians of the land surrounding the Manning River and its associated valleys are the Birpai people of the Bundjalung nation. That is factually incorrect. The Bundjalung lay far to the north separated from the Birpai by two other language groups.

To try to understand all this, I am constantly map checking. Herein there is now a problem. Whatever the strength of Google maps, it does not provide me with the right map size and detail that I need. What I really need is a good old fashioned Atlas that allows me to visually see the relationships between areas and especially rivers and mountain systems. Then and only then can I get full value from Google.

I accept that all this is probably a bit eye glazing, leading the reader to ask but does it matter? Yes, to my mind it does. If we can establish the broad pattern of Aboriginal life in Northern NSW and surrounding linked areas in 1788, then we have brought part of the Australian past into the light. If we do this, we have a better chance of interpreting some of the changing archaeological data, thus adding texture and depth to Aboriginal story over thousands of years.

ore it was too late. In doing so, she found a little of her mother’s remarkable story, including the reasons why Helen had put her aside for a period.

ore it was too late. In doing so, she found a little of her mother’s remarkable story, including the reasons why Helen had put her aside for a period.

Aboriginal students to acquire birth certificates. Such a simple thing, a birth certificate. Many people didn’t have one either because the birth went unregistered or because a certificate was not obtained. Now, the consequences can be dire because of the increasing rigidity of Government rules mandating a birth certificate as a key piece of evidence for just about everything.

Aboriginal students to acquire birth certificates. Such a simple thing, a birth certificate. Many people didn’t have one either because the birth went unregistered or because a certificate was not obtained. Now, the consequences can be dire because of the increasing rigidity of Government rules mandating a birth certificate as a key piece of evidence for just about everything.