On Sunday, the the Prime Minister, the Hon Julia Gillard MP, and the Deputy Prime Minister, the Hon Wayne Swan MP together released what was described as the Gillard Government's $1 billion Jobs Plan. The best short summary is here, the plan is here. I knew it was coming, but had forgotten about it until I received a cryptic sms message: "offsets mark how many?" I didn't understand and had to have it explained. Then I saw the significance.

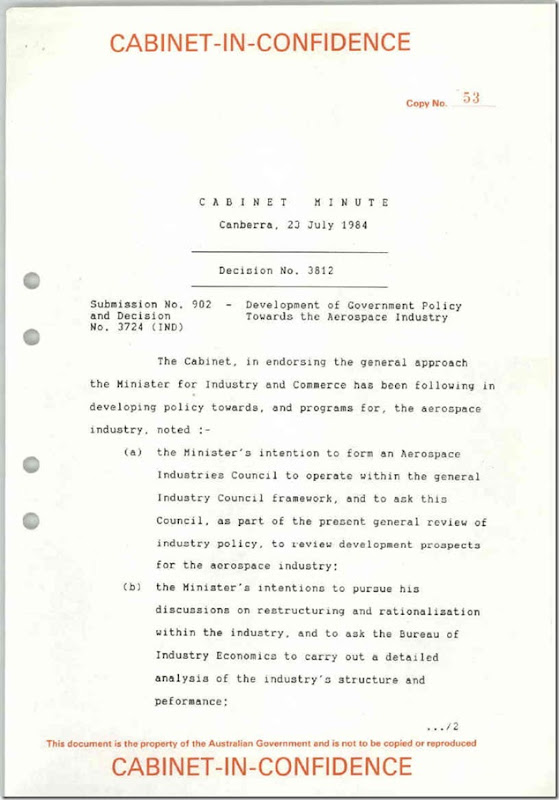

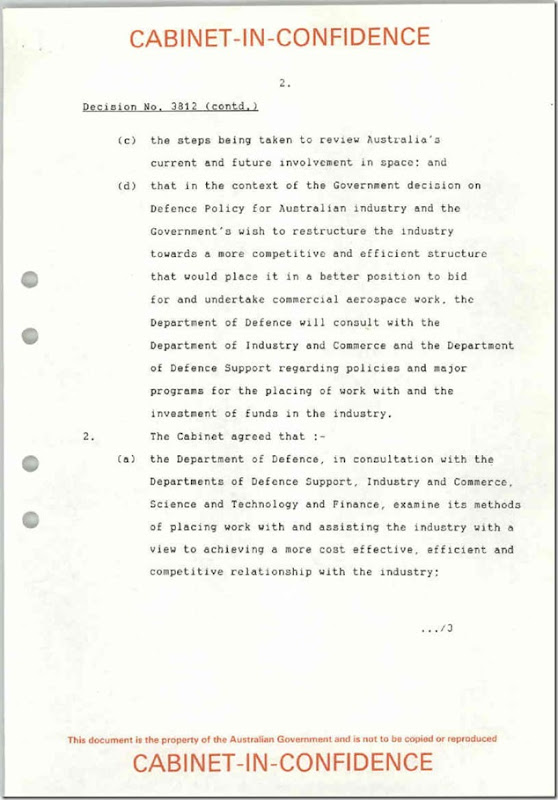

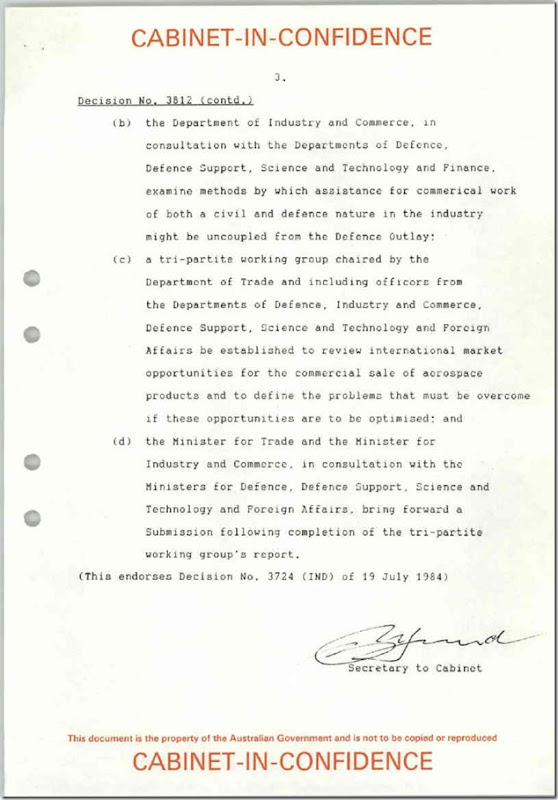

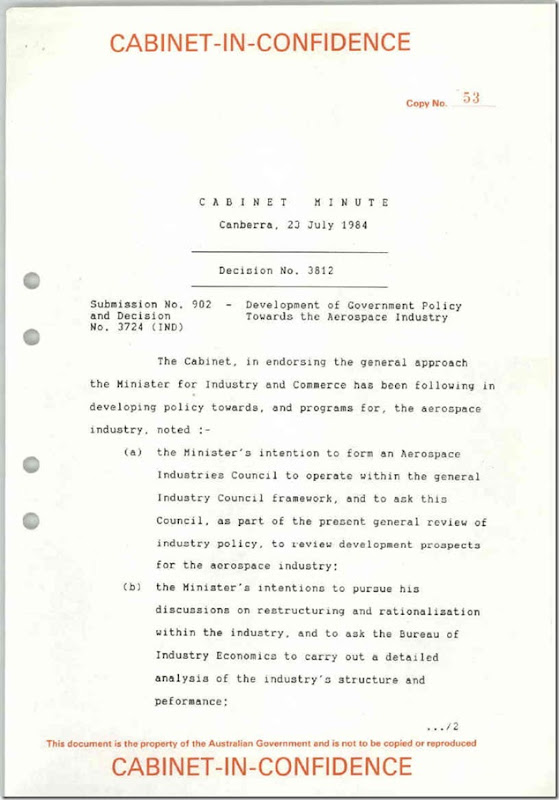

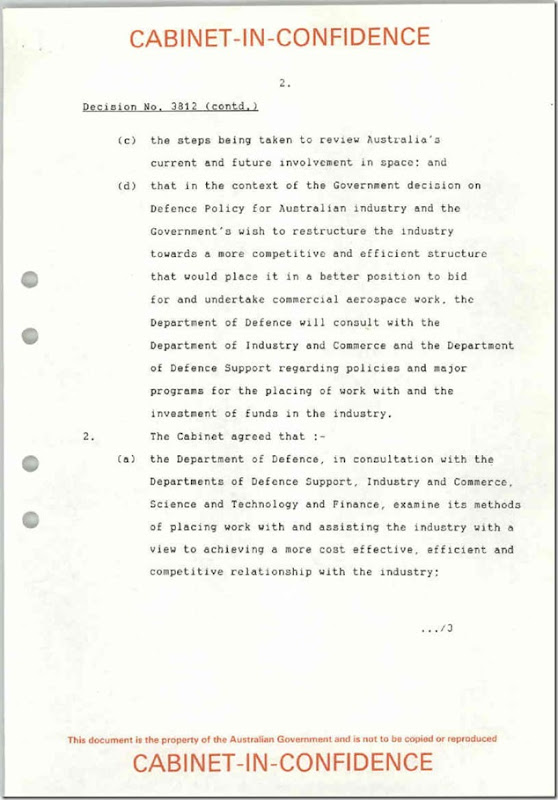

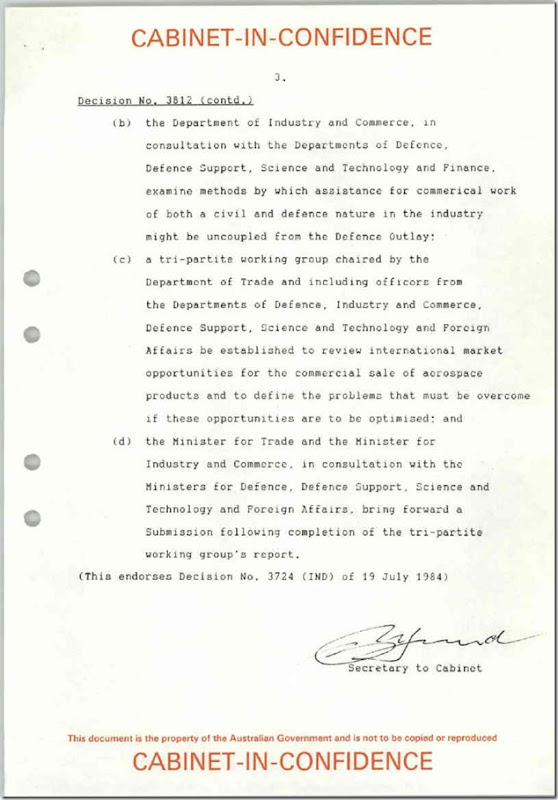

While there are some reasonable things in the statement, it made me very sad. I will explain why in a moment. But first, Australian Archives has begun releasing some of the industry policy cabinet submissions that I was responsible for. The decision that follows is from the first. If you click on this link you will find the decision. Just keep clicking on the page numbers on the bottom right and you will find the submission itself. Long, isn't it? Further comments follow the decision.

Now why did all this make me sad? Let me explain very briefly.

As the Department responsible for industry policy, the Department of Industry and Commerce was concerned that too much of its resources were tied up in policies and programs tied up in declining industries. The old industry protection regime had to go, the only questions where when, how, and what might take its place. I was asked to set up a new branch, the Electronics, Aerospace and Information Industries Branch. Our job was to look at development possibilities for a very large rapidly growing global sector combining manufacturing and services centred on electronics and system based industries.

To manage this, we decided that we had to treat the broad sector as a whole because of the interlinks. However, the sector was so varied that the best way of proceeding was by a series of individual sectoral studies. We could then focus on the common elements across sectors, as well as the unique features of each sector; this was part of what we called the matrix approach, one centred on the integration of all the policy measures affecting industrial development. In doing so, we assumed globalisation and reductions in industry assistance.

The aerospace submission and subsequent ministerial statement was the first in a series of which three have now entered the public domain; two have still to be assessed by Archives for full release. In the end, we failed to achieve our objectives. Here I will deal first with the particular and then the general.

If you read the submission. you will see a reference to Minister Button's forthcoming trip. We had been negotiating possible Australian participation in the development of a new airliner, the A320. Our industry was just too small to put up the development cash. Fierce opposition from Treasury made it extremely difficult to get funding. It was just too risky. Instead, in conjunction with local industry, we had worked out a game plan that might get Australia a carried share by trading off elements of the offset program. This required overseas majors wishing to sell airliners to local carriers to place certain work in Australia.

It was all set up. Then the CEO of Airbus arrived late and well under the weather for his meeting with Minister Button. Opening a bottle of champagne, he invited the Minister to have a drink. Angry and feeling that there was no point, the Minister left. On small things, do such big things fail. And what happened to the A320? I quote from Wikipedia:

As of December 2012, a total of 5,402 Airbus A320 family aircraft have been delivered, of which 5,234 are in service. In addition, another 3,629 airliners are on firm order. It ranked as the world's fastest-selling jet airliner family according to records from 2005 to 2007, and as the best-selling single-generation aircraft programme.

Effective industry policy is a grind. So long as you have the measure broadly right, then you can refine and target. But you must have continuity. It takes industry from seventeen months to seven plus years to get a new product or service out. If you shift the goal posts during this period, you are likely to invalidate you whole program. We held the line for four years, but that was as much as we could manage. Some elements of our approach lasted for much longer periods, but the integration that had been central was lost.

I know that I have written about this before, but the question of the best way of maintaining the continuity required for longer term success in both public and private sectors continues to exercise my my mind. The same issues arise in, say, higher education where the whole sector has been victim to constant change. Continuity does not preclude change. Just the opposite. You have to refine all the time. But that is a very different thing from from the sharp changes in direction that have been such feature of policy or management over recent years.

If you look at the latest policy statement, the ideas are not new. Some have been tried many times. In the case of the offsets/industry participation components, I have lost track of the various policy shifts over the last thirty years. Further, to my mind, the statement does not establish a proper nexus between what is proposed and the underlying dynamics of industry performance. Despite its wrapping in the language so beloved by modern governments, it is actually a very old fashioned approach.

This doesn't mean that all the ideas are necessarily bad. But who in business would base any actions on them? Unless Mr Abbott endorses the specifics, the opinion polls suggest that the whole thing will be overthrown by the end of the year. Even if Labor wins the elections, who would rely on their continuity?

That's my problem. How do we get continuity back?

Postscript

Both kvd and Winton Bates made useful comments on this post. In responding, I want to point to some of the complexities involved in the whole thing.

Winton referred to Australia's problems with the Collins class submarines. You will get a fair picture of the difficulties from the Wikipedia article.

One of the problems in this type of analysis is to decide what the real problem is.

The Defence Procurement Case

Take Defence procurement. Before going on, if you read the various attachments to that rather long cabinet submission, you will actually get a rather good snapshot of Defence plans and procurement at the time.

You start with boys with toys. Defence has needs, those needs are set within a strategic context as defined by the Government. They are also set within a budget context. While Defence is sympathetic to the idea of buying or building locally, they first look at what they really want in terms of capabilities. That has then to be modified in the context of a budget constraint. If Government wants something to be built locally for industry development purposes, Defence will say to Government during the concept definition phase, okay, but that will cost more. You, the Government, find a way of paying for that. If the Government does, or if it directs Defence to do it anyway by cutting out other projects, then the incremental cost is clearly industry assistance and should be judged as such.

In considering new procurements, Defence has a problem because of the combination of the increased cost and lumpiness of major Defence procurements. Mostly, the orders are not large enough to support local design and development. The difficulty then is to guarantee the life of type support that Defence to support the new acquisition over its long life. This covers all sorts of things: access to intellectual property, spares, maintenance with its specialist skills, capacity to do modifications etc.

The support requirements for each potential contender are different. Again, Defence can't get everything it wants in an ideal world without paying a lot of money. It has to make choices. Priorities have to be set. So Defence created as part of its tender process what it called Australian Industry Participation segments in tenders. Later, this term would be adopted more broadly, the context would change. This is an example.

The key point about the Australian Industry Participation Plans, and I would write several of them as a consultant, is that their purpose was not actually industry support, but the creation of a competitive environment in which the bidders would seek to meet Defence's support needs as defined in the most cost effective way relative to their particular kit offering.

Now factor in the work that we were trying to do in 1984. We had no money to sweeten the pot, although we were trying to create an aerospace industry development fund. We really didn't have the skills nor the power to say that this Defence choice was best from an industry development viewpoint, it will cost this much extra, and that cost needs to come from the budget. The only power we had was our capacity to make life difficult for Defence at the margin. All we could do is to say please take industry development considerations into account, these are the industry features we are looking for, can you help?

In fact, thinking about it, we did have another lever, but that would detract from my present analysis, so I will put it airside. I want to focus on the procurement issue since that is one that is central to the Government's approach.

The issue of Australian industry involvement in major projects has been a political issue since at least 1980. There have been multiple and shifting attempts to address the issue. Few have had positive results, partly because very few public servants have the time, or indeed the skills, to address the fundamental economic impediments involved, more because the issue is so multifaceted.

Our ability to make life difficult gave us a certain influence. Further, there were many in Defence who were highly sympathetic to the idea of increased Australian industry involvement. After all, the decline in Australian industry capacity actually created problems for Defence in providing proper life of type support. This was very different from attitudes among those concerned with, say, IT purchase. So what could we do?

We began by trying to understand the Defence procurement process. This was incredibly complicated, making it difficult to understand. It was also very lumpy. From an industry viewpoint, ,this meant floods followed by long droughts. It was small by global standards, meaning that local demand was insufficient to easily support sustained activities. It was also an expensive market place in marketing terms because of the very high cost of tendering, adding to difficulties for the smaller local industry.

One obvious thing that we thought about were impediments in the procurement process itself. One might be lack of information, although that one was being addressed. A second obvious one was the way that the tender specifications were written in terms of requirements. Were there issues here that might impede local industry? To a degree, the answer was yes for some tender requirements were actually written prescriptively around certain types of supply. This is still a current issue; Australian engineers argue that with more and more construction work going to overseas firms, engineers in those firms write the detailed specs in terms of the supplies they know. Often, this excludes Australian suppliers.

So there are some things that can be done to improve the procurement process from a local perspective. This is where so much policy concentrates. But it's not enough and that's why this element of the latest industry package is unlikely to have significant economic impacts. What else might be done?

We obviously had no control over the very choppy and variable nature of the procurement process. You can't tell a Government that it really shouldn't vary planned activities for either budgetary or political considerations just because it might damage Australian industry. Things don't work like that. So we needed other choices.

One choice was to improve productivity. Were there ways of lowering industry costs? This had general and particular implications. The general level of productivity in the Australian economy and the policy actions that might affect that were way outside our control. We might provide input, but really this was an area that we had to take as a given. Were there things that we might encourage in areas like skills? Yes, but they were all support measures.

In the most basic sense, we had just one option. We had to find a way of supporting the growth of the aerospace industry. If we could do that, then the industry would be in a better place to bid for participation in local defence business, gaining some additional cream. Here there were two not necessarily mutually exclusive choices. We could find a way of growing the aerospace industry's defence export exports. This had obvious political issues, but we could argue against those. Or we could grow the civil side of the industry, thus providing base to support the more variable defence business.

If you look at the submission you will see some of this.

.jpg)