It is, I suspect, something of a curse to be blessed with an interest even obsession in family history. It is more of a curse to find that one's own agendas have in fact been set by a family past, agendas reinforced by the very act of discovery.

To set a context for what follows, a modern shot taken in September 2011 showing me beside the big Maori war canoe in the Auckland Museum.

I am probably one of the few people who have sat in this canoe, at least in modern time.

I mentioned Uncle Vic Fisher in my last post, Musings on photos past 4 - Puhoi & Tahekeroa. He was curator of ethnography at the Auckland Museum and took my brother and I in one Sunday when the museum was closed and allowed us to sit in the canoe. I must have been around eight at the time.

In an earlier post on family history I said that the Belshaws were an Imperial and Commonwealth family. Doesn't that sound grand? Well, it's not quite like that. We weren't an imperial family like, say, the Murrays. Rather, we were a family to whom the Imperial and Commonwealth connection opened up opportunities, a small family that spread across the dominions.

This photo was taken in, I think, 1935 or 36. The inscription on the back reads "You are quite welcome to two cups of tea at 103. when you come over ER." I think that it was sent to Dad just before he left for England on scholarship.

Walthew Lane is one of the Belshaw streets, Platt Bridge along with Ince and Abram are places where the Belshaws lived. All are suburbs of Wigan.

This is the gritty world of industrial England. The card was sent just before or around the time writer George Orwell stayed in Wigan in February 1936, researching the book that would become The Road to Wigan Pier.

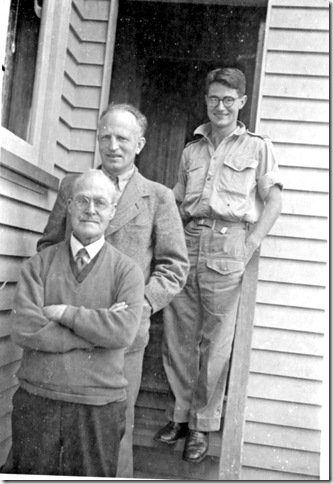

By now, my part of the Belshaw family had broken out of the industrial poverty trap. Emigration and education were central to that. The next photo taken in Auckland (New Zealand) in 1943 shows three generations of Belshaws. In front is grandfather James Belshaw, behind him Uncle Horace Belshaw,

James Belshaw was born on 6 February 1867. He started work at the pit head and went below ground at eighteen. He was the third generation of Belshaws to do so. He remained working there until sometime after his marriage at the age 30. His wife, Mary Pilkington, was a weaver in the mills at the time of her marriage.

Today we are used to mass education. We forget that this is quite new. My great grandfather James Belshaw's likely wedding certificate (27 June 1850) has only marks, no signatures. When my father visited his Aunt Ellen in 1936, his father's elder sister explained that her inability to write meant that she had lost touch with her family.

Grandfather James Belshaw could write and seems to have been ambitious, as well as strongly religious. He left the mines and became a greengrocer.

On Monday 3 April 1905 he stood for the Abram Council as a candidate for the new Labour Party . A leaflet produced by him stated:

Reasons why you ought to vote for Belshaw.

1. Because he is a life long resident among you.

2 Because he himself is a working man.

3. Because he goes in for Direct Labour Representation.

4. Because he is the choice of workers.

5. Because he Disbelieves in Cliqueism.

6. Because his Principles and interests are identical with yours.

In July 1905, a bit over thirty years before Orwell visited Wigan, James Belshaw sailed for New Zealand. This family photo was taken in 1905 before his departure. In front is Uncle Horace (b1898), with Mary holding Aunt May. (b1904).

The family followed a little over twelve months later. My father was born in New Zealand in 1908.

I have always wondered a little if the family would have broken out of the poverty trap had they stayed in industrial England. I suspect they would have, but I doubt that they would have had the opportunities that opened up in New Zealand.

Given their backgrounds, my Belshaw grandparents had a strong belief in education. They also focused on security. All three children initially became teachers, a secure job. When Horace as eldest wanted to give up a secure teaching position to become a WEA (Workers Educational Association) tutor, his parents were distressed. Later, they opposed my father's desire to become a journalist.

I can understand my grandparents' concerns. They knew industrial England, whereas the children had grown up in the more open environment of early New Zealand. They had a different perspective, although my own father's concerns about job security were deeply entrenched.

I am out of time today. I will continue this post tomorrow.