For those who celebrate Christmas, I hope that you had a happy time. May 2013 be a good year for all of us!

As always happens, the run up to the Christmas season in the media was marked by reflections on the year past and the prospects for the year ahead. I guess that I was no different, although I have been taking a short break from blogging. So this morning I am going to take you for a short idiosyncratic wander through the year past and year ahead.

Over at Club Troppo, Paul Frijter's The best news of 2012? posed this question:

Here is a question to put to you over Xmas time, the season of joy and hope: what has been the best news for you this year in the sense of the most uplifting development in Australia or the world?

My nomination was the always slow and often very fragile improvement in the human institutions designed to prevent conflict and reduce injustice, including especially injustices perpetrated on people by their own governments. It is easy to lose sight of this when we look at some of the examples around us, but the progress is there.

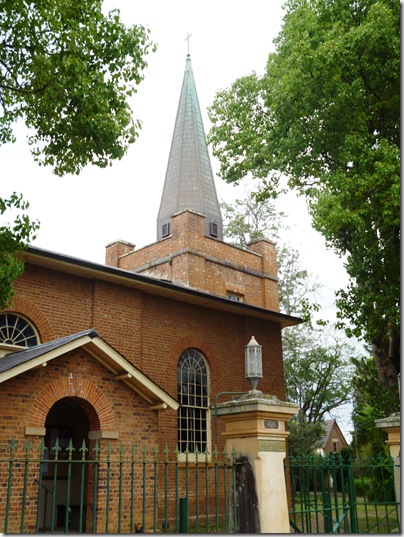

On the negative side, the thing that made me saddest in 2012 was the destruction wreaked on the historic buildings in Timbuktu in the name of religion. This may sound such a small thing compared to other tragedies, but I took it personally.

I have always wanted to visit Timbuktu. This is (was?) the Sankoré Madrasah. When I was a child, my father used to talk about his desire to visit Timbuktu. It was a place of mystery and remoteness. Somehow, I absorbed this romantic image.

Anybody who reads this blog on a regular basis will know of my love of history. It fascinates me. I love the patterns and linkages, I love the discovery of new things, I really like the way my knowledge builds. I have never been to Africa, let alone Timbuktu. As I read the newspaper reports, I felt a sense of dismay, that I had left my run too late.

That reference to newspaper reports provides a segue into another thing that made me sad in 2012, the continuing slow death of the newspaper. Again, this one affects me personally.

In January, I was taking pleasure that my long-running Belshaw World column in the Armidale Express had been used as a front page teaser in two consecutive editions of the Express. In February I and other columnists were unceremoniously dumped by the a new editor as part of a purge designed, in his mind, to make the paper more relevant to its local audience. In my case, I was replaced by a new column called the views of Gen Y. In September with another new editor, I returned to the paper with a another column, History Revisited, designed to add reader value in the magazine section of the paper.

In January, the paper was published three times a week, while my subscription came to me in print form. Now the paper is published two times a week and my subscription comes to me on-line. There you have a local microcosm of the broader media changes that I so often write about.

One thing that I have commented on in the whole change process are the risks of what we might call a search for relevance. Too often, the paper's readers are lost sight off.

Former Express editor Christian Knight had a very clear and accurate idea as to the demographic I appealed too; my readers were generally older and had strong local connections. They were also the people who bought the paper on a regular basis. Matt was new to the town and did not properly understand his market, applying generalised mental market models that did not accurately reflect local conditions. I came back with a specific mandate that really targeted my traditional readership demographic, although it was not put in that way. My own column is not on-line in public space, so to read it in the paper you have to buy either the print or digital version.

The progressive shift of the paper towards the Fairfax e-model has affected my writing. Put simply, nobody is going to buy the e-edition of the paper because of my column, although it may help retain subscribers. Attraction of new readers depends upon the print edition and people who buy a paper as a one-off or on an irregular basis. If I grab and hold them, they will continue to buy the paper, or at least the Wednesday edition I appear in. Then some, a few, may migrate to the digital edition.

So now in the column, I try to write for immediate impact. Instead of writing just for an established circulation, I need to grab the one-off or irregular reader at once. I need them to come back. Obviously, this helps Fairfax, but also meets my deep need to be read. So far, my current editor is happy with the results.

This change in writing is part of a broader change. The year now finishing has been a period of experimentation, of changing the way I write to better satisfy me and the people who do me the honour of reading my scribbling's. These changes centre on what I have come to think of as Jim, the story teller. It hasn't always been easy to write this year, my output is down, but I am happy with at least some of the results.

Returning to a broader canvass, the media changes that have taken place mean that I no longer bother with the Australian. I used to read the on-line version and sometimes buy the print version for its greater depth on particular issues. Now I don't bother with either unless there is a very particular reason for so-doing By contrast, I do buy the print edition of the Financial Review several times a week just because of the content.

The progressive changes in the mainstream media including TV have also changed my research patterns. Increasingly, I rely on fellow bloggers for leads or go to original sources that I already have access too. The mainstream media has bec

2012 was also the year of the e-book. In December, our fellow blogger Winton Bates published Free to Flourish via Amazon. He described the process in How easy is it to self-publish a Kindle eBook?. This post was one of a number of posts on both this blog and Winton's as we and others look for ways of broadening our reach.

More broadly still, on a number of occasions over 2012 I wrote somewhat sadly of the decline on the bookshop. The news here is not all bad actually, for book print versions are holding up well compared to other traditional media formats.

Let me illustrate.

This year I decided to give books as Christmas presents. I did so because I knew that those presents would be well received. Normally, I shop at the big Eastgardens centre near where I live. That centre no longer has a bookshop. Instead, I did my Christmas shopping at Parramatta near where I am presently working. With the closure of Borders, Dymocks there was absolutely packed, far more packed than most of the stores, with queues at all the check-outs. I watched for a while, trying to count up the value of sales. It was impressive.

So one bookshop is alive and well. More importantly, I would be quite astonished if Westfield's Eastgardens does not target a book store as a new renter. While the direct dollars here may be small in the scheme of things, the potential customer flow-on effects are potentially significant.

Looking back over my 2012 posts, two things stand out in an Australian political sense. One is the continued obsession with apparently simple measurable targets, along with a constant failure to achieve any of them. The second is the sheer nastiness that seems to have infected Australian political life. Expect more of the same in 2012, since there must be a Federal election at some point. Anthony Green has an interesting analysis here on timing and the constitutional position.

Some of the nastiest fights can be expected in the Federal electorates of New England and Lyne where the two New England independents who put the Gillard Government into power face major challenges and are responding in kind. This is an example from New England.

Despite the nastiness, there has actually been a steady increase in the depth and scale of policy and political analysis outside the hothouse worlds of the various Australian parliaments and the twenty-four hour media whirl that surrounds them. This actually has an impact over time for, in Don Chipp's words, it does help keep the bastards honest!

In economic terms, 2012 was a year in which the global economy actually did a little better than expected, the Australian economy somewhat worse. To my mind, 2013 is somewhat problematic in global terms because of the combination of restrictive fiscal policy with highly expansionary monetary policy. The world is awash with money that is likely to lead to inflation and asset bubbles. There is a de-facto economic arms race on centred on competitive currency devaluation.

This creates a very real risk that Australia will be squeezed in the middle. My best guess is that the Australian dollar will remain high. It's actually hard to see any other outcome at the moment. So expect more pain there.

Well, time to move on.

My strong personal thanks to my fellow bloggers and all our readers and commenters for their stimulation and friendship over the year. I had written a post - Christmas, friendship and the internet world - to try to describe this, but then decided not to publish it because it was too revealing in a personal sense for I was trying to show how the different slices of my life fitted together and the relationships between those slices and my writing and the differing interactions to be found in each slice.

Personally, 2012 was a tumultuous year. It was also a year in which I lived in a number of very different spaces. That's hard to explain. Seriously, the support I received over the year in both a personal and professional sense, the feedback I received from the things that I tried to do, the personal stimulation and the sometimes uncomfortable critiques, all created a depth and texture to my life.

There were responses on Facebook and Twitter, several thousand blog comments, many emails, cross-posts, gifts of books, invitations to speak or to visit and so it went on. Old friends re-established contact, new friends were made. Importantly, I found that old linkages between people were re-established, new linkages created. It was quite astonishing, and I struggled at times to respond.

To my mind, 2102 stands out as the year of friendship. And for that I am truly grateful!