It somehow seems appropriate that Sydney should celebrate the end of 2009 with a spectacular fireworks display whose sheer size made it hard to comprehend, especially when reduced to fit the small screen. At times, the different colours reflected on sky and water made for a completely surreal scene.

This photo from the Sydney Morning Herald gives something of a feel. You will find the full Herald gallery here.

Australians love to party. New Year's Eve 2008 took place against a backdrop of economic crisis This time there was a almost a feeling of triumphalism, of having escaped. House prices are up, the stock market has surged, employment has at least held, so let's party.

Like others, I enjoy the display. We had people round last night, watching the smaller fireworks display at nearby Coogee from the backyard. Then a little before midnight we gathered to watch the big display, a display that has already gone round the world - a flashy farewell to the noughties (CNN). The Sydney display has become big business because of the number of people involved (an estimated 1.5 million people watched from the ground), the size and the visual beauty of the back-drop. It guarantees Sydney prime time coverage across the globe.

Each year at this time, another set of Australian Government Cabinet papers is released. This, too, has become a major production with major local media coverage.

This year was the turn of the 1979 Fraser Government. Those papers provide something of a backdrop to this year's celebrations, drawing out just how much Australia has changed over the last thirty years. I thought that I might provide a few comments on the papers because we are now getting into years that I know quite well.

Jim Stokes, the National Archives historical consultant, has provided a very good overview summary of the events of that year. If you read this, you will see that many of the themes are very familiar today. It's just that responses have changed.

The photo (NAA: A12111, 2/1979/46A/1) shows Vietnamese boat people arriving in Canberra from camps in South East Asia for resettlement in Australia.

The then Vietnamese problems make today's boat people issues look like a pussy cat. The numbers involved were huge, the numbers that might have been involved larger still.

By July 1979, departures from Vietnam were running at 50,000 per month, while many Kampucheans were trying to enter Thailand.

The Australian Government was in a difficult position.

Refugee resettlement was politically unpopular; in February 1979, a Morgan Gallup poll found that 61 per cent of Australians wanted to limit the intake of refugees, 28 per cent wanted to stop it altogether. The Government had to take this into account, but was also worried about Australia's international reputation if we did not react. Then, too, there were humanitarian concerns, including worries that Asian countries would respond to the crisis by simply pushing the boats back out to sea. As it was, one estimate suggested that as many as 50 per cent of those leaving Vietnam actually perished at sea.

In the end, Australia took over 200,000 Vietnamese refugees to the Fraser Government's eternal credit. Importantly, there was very limited political backlash.

As it happened, over drinks last night I asked my brother-in-law when pubic opinion polls actually became a decision driver, rather than something to be taken into account and managed in forming policy. Neither of us was sure.

Zimbabwe (Rhodesia) was another international issue of great concern to Australia and again one that reflected Prime Minister Fraser's personal views.

In 1978 an internal settlement between the Smith regime and Bishop Abel Muzorewa was followed by an election in April 1979 which made Muzorewa prime minister. However, the army, police, judiciary and civil service remained under white control and the new government was disowned by the Patriotic Front of Robert Mugabe and Joshua Nkomo. It was also condemned by the United Nations and the Commonwealth Secretary-General Sonny Ramphal.

The situation was further complicated by the election of the Thatcher Government in May 1979 because there was the possibility that Britain would recognise the Muzorewa Government and end trade sanctions against it. This would split the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting to be held in Lusaka in the first week of Au

As it happened, Prime Minister Fraser played a pivotal role in negotiating an agreement at the meeting, culminating in the Lusaka Declaration on Racism and Racial Prejudice, which provided a re-statement of the British Commonwealth position in relation to Zimbabwe and paved the way for a resolution of the Zimbabwean issue.

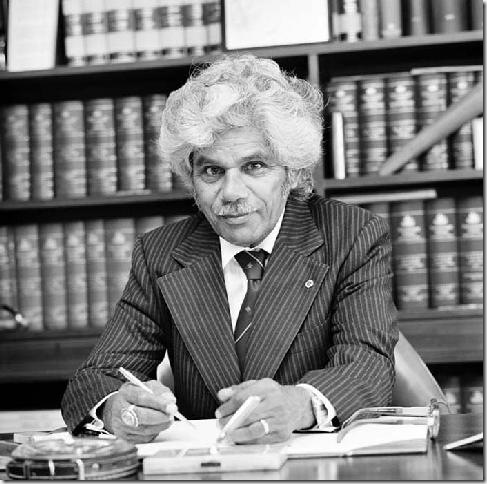

The photo (NAA: A8281, KN21/8/79/180) shows Malcolm Fraser and Secretary-General Shridath (‘Sonny’) Ramphal at the Lusaka, meeting.

As it happened, I was in London in 1979 at the time the subsequent Lancaster House meeting began in September 1979, laying the basis for a constitutional settlement. Then, last year in Shanghai, I watched the signature of the power sharing agreement in Zimbabwe.

I have read a lot of the blogs and other commentary from an African perspective. Despite this, as I watch President Mugabe continue to pontificate over the ruins of his country I am left with the uncomfortable and still unpopular feeling that Zimbabweans (and Africa more broadly) would actually have been better off if the Muzorewa had been recognised. Still, who could have known that Mugabe would be such a disaster.

One of the interesting things in reading some of the material, and this is going to sound an odd thing to say, is just how badly Australia was in fact bullied by its immediate Asian neighbours.

On the Asian side, Australia was seen as a fat, sluggish, arrogant, somewhat racist and declining European enclave. For its part, the Australian Government was trying to balance competing interests between the US and Asian connections and was remarkably sensitive to the way the country was perceived. Nobody foresaw the changes that were taking place that would leave Australia, arguably somewhat more arrogant, as a substantial regional economic and political power.

One of the most interesting parts of the Cabinet documents from a social change perspective are those relating to national symbols.

In February 1979, Cabinet considered a submission from Prime Minister Fraser on the observance of Australia Day.

The submission notes that Australia Day was not a success: the date (the landing by Governor Phillip) was seen as divisive by Aboriginal people (the phrase invasion day came a little later) and was not seen as really relevant to South Australia or Western Australia, while the organisation and promotion of the day was disorganised. Anzac Day, an alternative, was in decline because of changing attitudes towards Australian participation in war. The submission recommends a greater focus on Australia Day; Aboriginal objections were to be handled by a greater focus on nation building, not the arrival of Governor Phillip.

Who could have foreseen, certainly I did not, that Anzac Day would again become a huge national event, and that Australia Day itself (Aboriginal objections notwithstanding) would also become a major symbol of Australian nationalism.

The recognition of Aboriginal interests seen in the Australia Day submission was not unique.

In 1979 Senator Neville Bonner, the first Aboriginal person to sit in the Federal Parliament (photo NAA: A6180, 18/12/79/7), became Australian of the Year.

It's interesting how perspectives shift.

At the time I knew that Senator Bonner was the first Aboriginal parliamentarian, but I thought of him first as a senator. The question of his Aboriginality was secondary.

I make this point because when I read the cabinet submissions on Aboriginal issues I am saddened at the way in which things seem to have gone backwards.

Have a look at the submission entitled Report on the the National Employment Strategy for Aboriginals (link above). Sound familiar?

Now that I have finished my contract work with the NSW Aboriginal Housing Office I am again freer to comment on indigenous policy issues, although I have to be careful in commenting on things that I have actually worked on. Here I think that we need a new paradigm independent of injustice to Australia's indigenous people or non-Aboriginal guilt.

I have mentioned Joe Lane and his first wife Maria on a number of occasions. We came in contact because Joe was upset at the way Aboriginal peoples were so often presented as failures. In December, Joe had an opinion piece in on-line opinion. I quote the first part:

For a generation now, tertiary education has been the quiet success story for Indigenous people. Back in 1980, there were only about 400 Indigenous tertiary graduates across the whole of Australia, but by the end of this year, the total will be more than 25,000: that’s one in every nine or ten Indigenous adults.

Currently, enrolments and graduations are at record levels. Women especially are doing well - in fact, Indigenous women (aged 18 to 59) are commencing tertiary study at a better rate (2.45 per cent) than non-Indigenous Australian men (2.26 per cent).

With a boom in the birth-rate since the 80s, it is possible that a total of 50,000 Indigenous people could be university graduates by 2020. One hundred thousand Indigenous people could be university graduates by 2034 - this is certainly possible, and this could be one of the targets for the 25-year Indigenous Education Plan.

See what I mean? Where is the failure in this?

Finishing on a process note, as part of the release of the 1979 Australian Cabinet Records Patrick Weller had a fascinating piece on Cabinet processes. The piece may not be fascinating to the ordinary reader, so let me explain.

Malcolm Fraser was in some ways an impatient, get things done man, who loved Cabinet processes. The problem is, and this bears upon my criticisms of Kevin Rudd, he overloaded the system. Just look at the number of Cabinet submissions and memoranda and the time taken to consider them. There is very little time in all this for real thought.

Finishing with a personal story.

In 1979 I was interviewed for the position of Assistant Secretary, Economic Analysis Branch, in the Department of Industry and Commerce, a position that I got. Conscious that the Cabinet system was clogging up, I said in one point in the interview that our problem was that Cabinet was like a narrow water pipe down which we were trying to force more and more, leading to higher and higher pressure.

Both Neil Curry (Permanent Head) Alan Godfrey (Deputy Secretary) laughed. Then Alan said and very dirty water too!

No comments:

Post a Comment