In my continuing series on our Greek trip I have mentioned the close connections between Greece and Australia a number of times. These are links of blood and fire.

In Arrival in Iraklion I spoke of the Battle of Crete. At Christmas, my daughters gave me a copy of 100 Australian Poems you need to know (James Grant editor, Hardie Grant books, Prahran, 2008). This included one poem on Crete, The Tomb of Lt. John Learmonth, A.I.F. by Australian poet John Manifold. You can find a copy of the full poem here.

The poem begins:

This is not sorrow, this is work: I build

A cairn of words over a silent man,

My friend John Learmonth whom the Germans killed.

John Learmonth was the son of Victorian grazier, naturalist and historian Noel Learmonth. He and Manifold appear to have been childhood friends.

Schoolboy, I watched his ballading begin:

Billy and bullocky and billabong,

Our properties of childhood, all were in.I heard the air though not the undersong,

The fierceness and resolve; but all the same

They're the tradition, and tradition's strong.

In March 1941, Lieutenant John Learmonth 2/3rd Field Regiment, AIF, sailed for Crete as part of Lustre Force, a military expedition sent to help defend Greece from the Germans. The force included over 17,000 Australians as we

Learmonth appears to have absorbed the Greek romantic myth, something I have already written about in this series.

"A number of pretty little islands have been visible on our starboard quarter since daylight this morning," he wrote in his diary on 29 March 1941 as the troop ship sailed up the Greek coast towards Piraeus. He went on:

I have forgotten what little ancient history I ever read; but I fancy Ulysses must have sailed in these seas. I wonder did the Sirens live on one of those little islands over there, now slumbering so peacefully in the warm laughing sea; and do those rocks hide the caves of Cyclops, the one-eyed giant? What history has been made among these seas; what sagas of the human race have had their setting here. Thousands of years ago men have sailed these seas to go to war, and we sail them today for the same purpose.

The trip combined boredom with fear as the convoy was under threat from enemy aircraft and ships, including the Italian navy that had finally put to sea under pressure from the Germans. The day before Learmonth recorded his reactions, British and Italian naval forces clashed at Matapan. The Italians were heavily defeated, leaving the sea lanes to Greece open.

Australian poet Kenneth Slessor who was travelling with the Force as official correspondent described the first reactions to Greece in this way:

They find themselves in a country that might be a piece of Australia towed across the world. The Greek spring with its white and piercing light, its floods of sun, its clean sharp water and, above all its exiled eucalypts, is closer to home than anything they have seen since they left Fremantle.

All those years later, my own reactions to the Greek Islands including the gums was much the same.

I will write about the chaotic events of the Greek campaign in a later post. Outnumbered, Commonwealth and Greek forces were forced into a fighting retreat that included defence of evacuation zones. Between 24 and 29 April, the Mediterranean Fleet, including warships of the RAN, and attendant merchant vessels evacuated an estimated 50 732 men and women of the British force from five embarkation areas.

The evacuation ships came under constant attack from German dive bombers. On 25 April 1941 (Anzac Day) Able Seaman Patrick Bridges, RAN recorded in his diary:

Heading for Suda Bay [Crete] with other ships loaded with troops. Germans attacked us with heavy bombs. Soldiers sleeping all over the place. No sleep last night. Pulled alongside jetty to unload troops. Went alongside another big ship and unloaded another 1000 troops. Pulled alongside wharf again and then went out and anchored. Dropped down in a corner dead beat and fell asleep straight away.

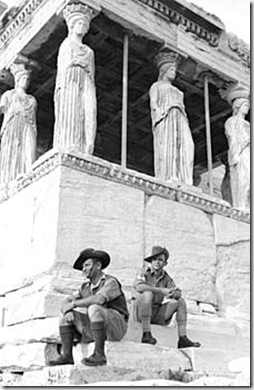

The next photo shows Army nurses from Australian and New Zealand

hospitals arriving in Suda Bay after their

evacuation from mainland Greece, April 1941.

By 28 April the Greek government of Prime Minister Emmanuel Tsouderos, along with the King, George II, had established itself at Hania in Crete. Major General Bernard Freyberg, the commander of the 2nd New Zealand Division, was appointed as the British commander-in-chief of what became known as ‘Creforce’.

On 29 April, John Learmonth returned to his historical musings in his diary:

It is only a quarter of a century since the Australians of the first A.I.F. made history here, yet this was the cradle of history before the Australians, or even the British, had come into being. I wonder shall we in our turn add fresh deeds to the story of mankind, deeds that will go down from generation to generation for thousands of years to come; and I wonder also what new races will rise up and fight their wars here, when we are as long-distant and forgotten as the Ancient Greeks … now seem to us.

In the fighting that followed, Commonwealth and Greek forces supported by the Cretan population inflicted heavy casualties on the Germans, so heavy that it effectively ended the German paratroopers as a military weapon. However, with German control of the skies, the military balance fell in their favour. Again, British control of the seas allowed for evacuation.

Some 500 British and Commonwealth troops remained behind and took to the hills. John Learmonth was one. Manifold records it this way:

There was no word of hero in his plan;

Verse should have been his love and peace his trade,

But history turned him to a partisan.

There Learmonth was killed.

Far from the battle as his bones are laid

Crete will remember him. Remember well,

Mountains of Crete, the Second Field Brigade!Say Crete, and there is little more to tell

Of muddle tall as treachery, despair

And black defeat resounding like a bell;But bring the magnifying focus near

And in contemtp of muddle and defeat

The old heroic virtues still appear.Australian blood where hot and icy meet

(James Hogg and Lermontov were of his kin)

Lie still and fertilise the fields of Crete.

One of his men wrote:

At the end on Crete he took to the hills, and said he'd fight it out with only a revolver. He was a great soldier.

As I researched this story, I thought of John Learmonth's parents. One son died in infancy. Then John died in Crete. His younger brother, Wing Commander Charles Cuthbertson Learmonth, D.F.C., was killed in 1944. Learmonth air force base in Western Australia is named after him.

Note on sources

In addition to the poem and some general web searches, this post draws heavily from 'A Great Risk in a good cause', the story of Australian involvement in the Greek campaign.

![clip_image002[5]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg63ldiVLQuFlxPUcv-swEoZTRu8l4vAd5yl55xVyhymh5-X9BviBeW7DF-9XttvNbDA2fUQ-LTjnP-hoaqptpzaC9lA5oxYEwku98AGu57ZoX6HLaxydvHJLHC6lnUK3cuPBWpgw/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image002[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjvoiZ605V_dAcnxT4iIW9pXfruOY5v3lRPl51UIEdeFgMQx_BqBHRd64rkNa1TUGW4PrUZ4DqqWvterYraQZYNkvAMtBHt_seO31JMcrUBXXK-2ZQQKKFHWKrjhZqdsxEQ-IrYUQ/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image002[3]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgQOvau2VFIgOdY3DTg-n87T2urk-g-XtT-DxBizKbwhOsh4SEJRIMFJqOplG5IlRKfPBtSanylIpX1z9TACQwHXhmOGgttkPrGrkQS-sxkiP9DiroRBMM7YRogZRN7FDKky8wA9g/?imgmax=800)