I had wanted to visit the Minoan site of Knossos for many years.

As a child, C W Ceram's Gods, Graves and Scholars fascinated me. First published in 1949 and still in print today, this history of archaeology played to my love of adventure and of discovery. Those early archaeologists were strange and fascinating folk. The discovery of the previously unknown, the possibility of treasure, was quite intoxicating. The excavation of Knossos by Sir Arthur Evans was part of that story.

I grew up in an Australian world that was saturated with history in a way that is, I think, not true today.

The Bible was one element of this. More people went to church and to Sunday School. By their very nature, the Bible stories stories provide an introduction to one slice of history. It may have been a partial view, something that I will return to in a moment, but it was a view.

In this context, it was interesting watching visitors from modern secular Australia struggle to come to grips with the continuing importance of faith and religion in modern Greek life. It wasn't just the number of churches or priests, nor the shops selling icons and beads, but the visible expression of religious faith, especially among older Greeks.

Religion and the history of Greece are inextricably entwined. Religion divided, but faith and the Orthodox Church were critical to the survival of a Greek sense of identity and culture through constant turmoil.

This photo is actually from Paros. It is a crowded photo, but it does give a feel for the age, the ornateness, of Greek religious expression.

A second element in that past sense of history was the Empire and Commonwealth itself. The Empire may have been in terminal decline, on the point of dissolution, but much of the map was still coloured pink when I was a child. When, as at the Battle of Crete Museum, I see the phrase "Commonwealth troops", it has meaning that extends far beyond the modern attenuated concept.

The effects of Empire and Commonwealth on thought and the sense of history were still quite pervasive. This is actually difficult to explain to a modern Australia sometimes obsessed with its own sense of identity where everything has to be squeezed into, or at least interpreted through, a purely local frame. History then did not begin in 1788 or a bit before, nor was it limited to just that taught. It came through in family connections, in books and comics, in popular novels, in the language and concepts used.

One element in that thought was a love of things classical. The English in particular fell in love with things Greek; not the Greece of today, but an idealised version of classical Greece. The English were not alone in this, it was a Western European phenomenon, but it was the English version that affected not just Australian thought, but Greek history itself.

Earlier I commented in the context of Bible stories that the history around me, while pervasive, was partial.

In this world, the combination of Christianity with love of things classical created an historical perspective that saw history as a process moving from the early great civilisations of the Middle East through Greek civilisation to Rome. Greece and the Greek city states were bulwarks against invasion from the east. Greek civilisation was central to the formation of the modern (read European) world. A truly educated person knew Greek as well as Latin.

By the time I was b

My secondary school in Armidale (The Armidale School) no longer taught classical Greek (Latin was still compulsory in the A stream), but it was less than thirty years since TAS had presented one of the classic Greek plays in Sydney in the original language.

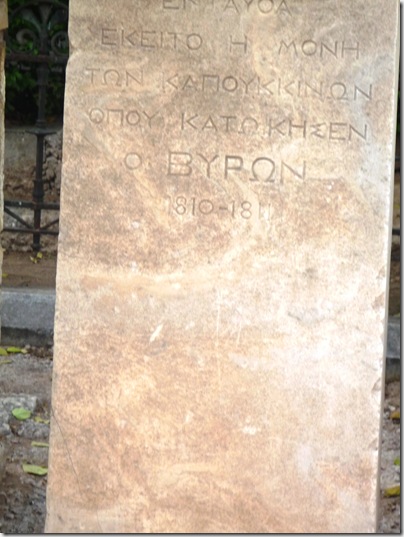

The English poet Lord George Byron (1788-1824) may, as Caroline Lamb famously said, have been mad, bad and dangerous to know, but he truly encapsulated and indeed became the symbol of the English love of things Greek.

To Byron, Greece was an ideal; the final fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans and the subsequent loss of the Greek mainland and Greek Islands to the Ottomans a disaster. He travelled to Greece to throw himself into the Greek rebellion against the Ottoman Empire. His death from fever in Greece added to his allure.

The Greeks justly regard Byron as a national hero, but it is a little more than that.

On the English side, Byron added emotional force to the Greek love affair. British policy in the Eastern Mediterranean was not driven just by geopolitical concerns, but also by the English love for and idealisation of things Greek. English attitudes were riven with contradictions, contradictions not limited to the political.

In the moralistic world of the Victorian Empire, there were deep suspicions about sexuality and especially sexual relations between males. This contrasted with attitudes in classical Greece where sex between men, and between men and young boys, was seen as normal.

This played itself out in the complicated world of the English (and Australian) boarding school. There a contained environment contrasted rigid Victorian morality with very contrary Greek thought and attitudes; the resulting tensions can be seen clearly in books such as E F Ben

On the Greek side, the European and especially English attitudes towards classical Greece became an element in the highly emotional cocktail involved in the creation of modern Greece.

Greece was a new entity, one that had not existed before in political terms. in creating Greece, the Greeks' combined a vision of classical Greece with that of the Byzantine or Greek Empire. They were recreating Byzantium on a classical base.

This vision affects Greece today. That strangely named political creature, The Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, is named that way because Greece will not, cannot, accept another country with that name.

To the Greeks, Macedonia is both enemy and part of Greece. Macedonia sat on the outskirts of classical Greece. Philip of Macedon and especially his son Alexander were conquerors, outsiders, but also people who spread Greek influence. Modern Greece rests its claim for existence, its historical role, on the combination of classical Greece with the Alexandrian and Byzantine Empires. To accept a country simply called Macedonia is to deny that historical imperative.

I may seem to have come a long way from my starting point to this post, Knossos and the Minoans, and in one sense I have. However, there is a link.

My interest in Minoan Crete is not just the sense of discovery going back to Ceram's Gods, Graves and Scholars. It's rather more that here is a civilisation that did not quite fit in, that pre-dated the historical models that I had absorbed. Greece was more than just Athens or Sparta.

I will continue the story in my next post in this series.

4 comments:

I am enjoying these posts on Greece, Jim. I expect that other readers of your blog are also enjoying them too.

Thanks, Winton. Despite the time involved, I am enjoying writing them. It is nice to know that someone else is, too.

Hey, me too!

Thanks, Randy!

Post a Comment